Jamie has always been a happy wee boy, interested in everything, loves stories. But when he started school something died – the light went out in his eyes. (Mother of 5-year-old boy.)

The teachers say our daughter has settled in well – everyone’s happy with her progress. But we’re seeing a difference at home. She’s tired and not sleeping well, more anxious than she used to be. She’s never been a particularly tantrummy child but we’ve had quite a few lately. (Mother of girl, 4 years 10 months.)

William told me he gets into trouble at school quite a lot – he’s ‘naughty’. I asked why that was because he hadn’t been naughty when he was attending our nursery. He replied, “That’s because you don’t know me now. I was littler then. And I never thought this is what I would grow up as…’ (Nursery head teacher; William is 5 years old.)

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

Starting school at the age of four or five causes problems for many children. A growing number of research studies have linked an early start on formal education to social, emotional and mental health problems in later childhood and beyond1. An increasing number of Scotland’s children and young people now suffer from developmental disorders and mental health conditions.2 The reasons behind these problems are complex, but we cannot ignore the impact of pressure for early academic attainment.

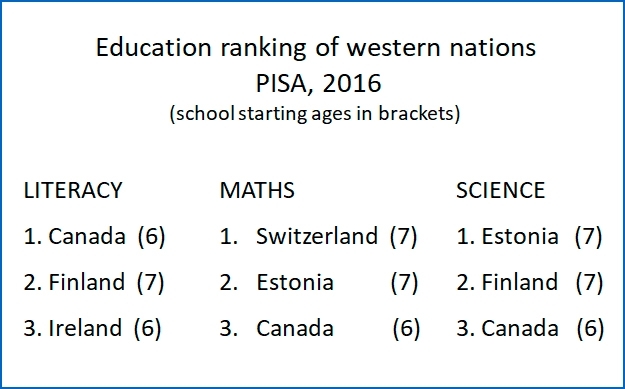

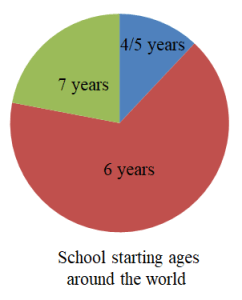

Yet there is no educational advantage to an early start. Indeed, in 88% of countries worldwide, children don’t start school till they are six or seven – and countries that wait till seven (such as Finland, Estonia and Switzerland) always do well in international comparisons of educational achievement. Research has found that children who are taught literacy skills from the age of five do no better in the long run than those who start at seven3. The results even out by the time they’re 10 or 11, and thereafter the late starters tend to have better comprehension skills and are more likely to enjoy reading.

Yet there is no educational advantage to an early start. Indeed, in 88% of countries worldwide, children don’t start school till they are six or seven – and countries that wait till seven (such as Finland, Estonia and Switzerland) always do well in international comparisons of educational achievement. Research has found that children who are taught literacy skills from the age of five do no better in the long run than those who start at seven3. The results even out by the time they’re 10 or 11, and thereafter the late starters tend to have better comprehension skills and are more likely to enjoy reading.

An early start also encourages early testing. Concern about the achievement gap between rich and poor has led the Scottish government to introduce national standardised assessments in literacy and numeracy, starting at P1 when children are four or five. Yet there is plenty of evidence that testing children at this age has no statistical reliability; it does, however, lead to greater concentration on specific skills teaching; growing anxiety on the part of parents, teachers and children; and less time for what research tells us the under-sevens really need: learning through play4.

THE TESTS AND TARGETS TRAP

Introducing the Scottish government’s policy on testing in September 2016, the First Minister insisted that ‘This is not about narrowing the curriculum or forcing teachers to “teach to a test”… the assessments will inform teacher judgement – not replace it.’

However, every country that has so far introduced national testing in primary schools has seen a narrowing of the curriculum, a steady increase in teachers ‘teaching to the test’ and a push-down of academic content to ever younger age groups. These developments are related to the inevitable linking of national assessments to targets for attainment at specific ages.

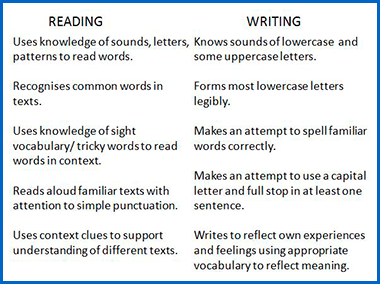

Draft lists of literacy and numeracy skills, known as ‘benchmarks for achievement’, were published in Scotland in 2016 and updated the following year. The P1 literacy benchmarks do not bear much resemblance to the content of Curriculum for Excellence’s Early Level for the three- to six age group, which stresses the centrality of exploration and play. (Indeed, the first draft of the benchmarks bore a strong resemblance to a list of targets devised for English five-year-olds.)

Most early years authorities would argue that age-related ‘standards’ in literacy and numeracy are not appropriate for children under the age of seven. Yet their introduction has reinforced the deeply-ingrained cultural belief in Scotland that, as soon as children start school, they should start work on the 3Rs. Within a few months of the benchmarks’ appearance, ‘Help your P1 child with literacy/numeracy’ workbooks for parents appeared in bookshops, just as they did in England when its tests and targets regime began a couple of decades ago.

The First Minister also pointed out in her speech that many local authorities have been imposing ‘baseline testing’ systems on schools for years and that, by replacing these, the national assessments would provide national data while reducing teacher workload.

However, whether a tests-and-targets agenda is imposed at national or local level is irrelevant. If P1 teachers are required by their senior management to ensure that as many children as possible achieve the targets/benchmarks, it inevitably affects their relationship with children and makes it impossible to provide a developmentally-appropriate, play-based curriculum. Upstart believes that local authority baseline testing is partly responsible for the failure of most Scottish schools to turn the play-based principles of Curriculum for Excellence’s Early Level into practice over the last decade.

As a recent report from England points out (Baseline Assessment: Why It Doesn’t Add Up) it is increasingly clear that the data provided by standardised testing of such young children has little or no statistical value. Even the Westminster parliament’s education committee has now ‘urged the government to be cautious in introducing a baseline measure’ and has recommended that ‘it should only be carried out through teacher assessment’ (that is, through observation of children’s behaviour, backed up by professional judgement).

EARLY YEARS AND THE EARLY LEVEL: WHERE DID IT ALL GO WRONG?

In UN policy documents5, the term ‘early years’ refers to the period from pre-birth to age eight, ‘a time of remarkable growth with brain development at its peak… [when] children are highly influenced by the environment and the people that surround them’. In Northern European countries, children spend three or four of their early years in relationship-centred, play-based ‘Early Childhood Education and Care’ (ECEC) before transferring to school at age six or seven.

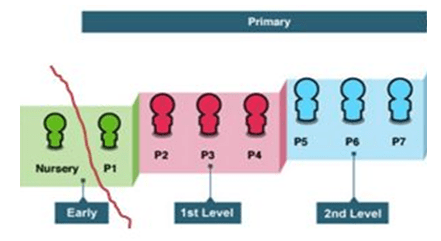

Scotland’s ‘Early Years Framework’ also defines the early years as extending to eight years of age, and Curriculum for Excellence’s ‘Early Level’ covers a significant chunk of it (from age three to six, with provision to extend to seven or later where appropriate). If Scottish schools had, from the establishment of Curriculum for Excellence in 2010, embedded the play-based principles of the ‘Early Level’ into P1/2 practice, we would by now be providing a similar form of ECEC to the other Northern Europeans.

However, culturally-ingrained habits die hard. The national assumption that ‘school means the 3Rs’ continued to lead parents, politicians and the media to expect that children would crack on with reading, writing and sums as soon as they arrived in P1. This was reinforced by the political ‘silo effect’ because the Curriculum for Excellence‘s Early Level is split right down the middle.

- The first half is nursery education, which is under the guidance of the Care Inspectorate and is often, in political and media discourse, referred to as ‘childcare’.

- The second half is Primary 1, which falls within the remit of HMIe (Inspectorate of Education) and culturally associated with formal schooling.

As a result, early years education in Scotland is not regarded, and has never been able to operate, as a coherent whole and the voices of early years educational experts have seldom been heard. Over recent years the term ‘early years’ has been conflated with ‘childcare’ and assumed to apply just to the year or so that children spend in nursery. There also has been a significant decrease in the number of qualified teachers working in nurseries and the many highly-qualified ECEC practitioners who do work there are seldom accorded much attention in the educational or political world.

The fragmented nature of the Early Level, combined with top-down pressure for an early start on literacy and numeracy skills from politicians, local authorities and senior management higher up the educational pecking order, has ensured that play-based learning has been sidelined in most P1 classrooms. Indeed, as parents have become increasingly concerned about their off-springs’ education, it’s being sidelined in many nursery settings too.

In later-start countries with well-established kindergarten systems, the ECEC sector has a far greater voice and this has influenced public opinion. It is widely accepted in Northern Europe that, between the ages of three and six/seven, the educational emphasis should be on children’s physical, social and emotional development, outdoor play and ‘the joy of learning’. It would therefore be unthinkable to introduce standardised assessment of literacy and numeracy for children under the age of seven. We have often heard Early Years teachers from Germany, the Netherlands and the Nordic countries describing the UK’s early start on the three Rs as ‘wrong’, ‘mad’ and ‘cruel’.

In later-start countries with well-established kindergarten systems, the ECEC sector has a far greater voice and this has influenced public opinion. It is widely accepted in Northern Europe that, between the ages of three and six/seven, the educational emphasis should be on children’s physical, social and emotional development, outdoor play and ‘the joy of learning’. It would therefore be unthinkable to introduce standardised assessment of literacy and numeracy for children under the age of seven. We have often heard Early Years teachers from Germany, the Netherlands and the Nordic countries describing the UK’s early start on the three Rs as ‘wrong’, ‘mad’ and ‘cruel’.

EARLY YEARS AND THE ATTAINMENT GAP

Upstart Scotland shares the First Minister’s deep concern about the poverty-related attainment gap. By the age of five in Scotland, there is already a gap between children from high and low income families of around 10 months in problem-solving skills and 13 months in vocabulary6. The explanation is sadly obvious: for very many reasons, parents struggling to raise their children in poverty are unable to provide the same sorts of experience and support as those in more advantaged circumstances.

While the problems of ingrained poverty cannot be solved by education alone, excellent Early Childhood Education and Care could make a considerable contribution. However, as long as Scottish children are expected to make the transition from a nursery setting to a formal school environment (with an emphasis on literacy and numeracy) when they are only halfway through their early years, disadvantaged children are unlikely to catch up in terms of problem-solving and language development. This is why Upstart Scotland is campaigning for a developmentally-appropriate kindergarten stage for children between the ages of three and seven, based on the successful Northern European models.

In a relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten environment, practitioners can ensure that all children have access to the type of experiences through which young human beings naturally develop problem-solving, vocabulary and language skills:

In a relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten environment, practitioners can ensure that all children have access to the type of experiences through which young human beings naturally develop problem-solving, vocabulary and language skills:

- motivating play activities, explorations and investigations, involving real-life problem-solving and discovery of number and maths

- plenty of social interaction with other children and supportive adults, including daily opportunities to share songs, rhymes and stories.

As children become interested in reading, writing and numbers, practitioners can support and develop that interest as appropriate to the individual child. In countries where formal education doesn’t begin till seven, many children are already able to read, write and reckon by the time they start school and the overwhelming majority are ready to learn quickly and successfully.

However there are many other aspects of children’s development during their first seven years which are just as important as laying the foundations of literacy and numeracy, all of which are developed through play:

- physical fitness, bodily control and coordination, and physical self-confidence

- personal qualities, including perseverance, risk-management skills, self-regulation and emotional resilience

- social and communication skills, such as getting along with other children and the ability to work collaboratively

- creative and cognitive capacities, such as using a variety of media (including language) to explore and express their ideas, and embodied ‘common-sense’ understanding of the world and how it works.

Children from disadvantaged homes are also more likely than others to experience developmental delay in these aspects, but there’s gathering evidence that – as a result of lifestyle changes in recent decades – we need to provide more support for all young children’s physical, social and emotional development.

THE CRITICAL IMPORTANCE OF SELF-REGULATION AND RESILIENCE

The Curriculum for Excellence defines ‘four capacities’ to which it aspires for every Scottish child: successful learner, confident individual, responsible citizen, effective contributor. The foundations upon which these capacities are built are laid in early childhood, and if we neglect the wider aspects of Early Level learning listed above, the rest of the educational process will be based on very shaky ground.

There are two aspects of child development that are of particular importance in ensuring children’s educational success and long-term health and well-being.

- SELF-REGULATION

Self-regulation is an aspect of the brain’s ‘executive function’ which, according to the Harvard Centre for the Developing Child, is not fully established until children are around seven years old. It is related to physical control and coordination, as well as to social and emotional development.

Today’s four-year-olds are generally more sedentary, less active and therefore less physically well-coordinated than previous generations. Due to Scotland’s very early start on desk-based learning, many children now struggle with self-regulation in the classroom. This means that, when confronted with a situation that is developmentally beyond them, they have two choices: they can either ‘challenge’ the teacher, in which case they run the risk of being labelled ‘disruptive’, or they can find some way of complying with adult demands.

Today’s four-year-olds are generally more sedentary, less active and therefore less physically well-coordinated than previous generations. Due to Scotland’s very early start on desk-based learning, many children now struggle with self-regulation in the classroom. This means that, when confronted with a situation that is developmentally beyond them, they have two choices: they can either ‘challenge’ the teacher, in which case they run the risk of being labelled ‘disruptive’, or they can find some way of complying with adult demands.

It is clearly unfair to describe children who are developmentally incapable of regulating their behaviour as ‘challenging’. Indeed, it has been recommended by psychologist Suzanne Zeedyk that we should stop using the term ‘challenging behaviour’ for young children and instead talk about ‘distressed behaviour’.

However, in a culture where four- and five-year-old children are expected to achieve the standards described in the benchmarks (see above), teachers feel obliged to insist that they sit at desks, behave like school pupils and practise the various skills involved. Nowadays, it is common for Scottish P1/2 classes to use ‘behaviour management strategies’ – systems of reward and punishment – so that children learn to comply with these adult demands. Thus, rather than becoming the intrinsically-motivated ‘successful learners’ that CfE describes, they learn to pursue extrinsic rewards such as ticks, stickers and smiley faces.

The use of behaviour management strategies (such as the ‘traffic light’ system, where children are ‘on green’ if behaving well, but move up to amber or red if they don’t conform) also prevents many of them from turning into ‘confident individuals’. We began this paper with quotes about three children who had clearly found the transition to this type of behaviour control very difficult, resulting in feelings of anxiety or shame – and there are many more such stories.

The use of behaviour management strategies (such as the ‘traffic light’ system, where children are ‘on green’ if behaving well, but move up to amber or red if they don’t conform) also prevents many of them from turning into ‘confident individuals’. We began this paper with quotes about three children who had clearly found the transition to this type of behaviour control very difficult, resulting in feelings of anxiety or shame – and there are many more such stories.

Our early school starting age means that we in Scotland are culturally accustomed to the idea that early years teachers are – whether they wish to or not – obliged to use systems of control to keep children’s behaviour in check. Such systems are necessarily at odds with nurturing children’s love of learning, feelings of self-worth and personal capacity to self-regulate. And if these capacities are not nurtured in the under-sevens, it’s likely that there will be disproportionate reliance on behaviour management techniques throughout the educational system.

What’s more, if schools are, however inadvertently, causing some young children prolonged distress, anxiety or shame, this is also likely to impact on another critical aspect of early development: emotional resilience.

- RESILIENCE

Resilience is defined as the ability to deal with stress, rise to challenges and bounce back from difficulties. It is partly down to children’s individual nature (some people are more naturally resilient than others) but also to environmental factors, especially during the early years. These environmental factors can be summarised as:

- enjoyable, supportive relationships with the adults who care for them, which helps develop their self-confidence and positive self-image

- many opportunities to develop a sense of self-efficacy (which arises naturally from dealing with small, manageable risks and problems encountered during play)

- strong self-regulation and executive function

- a supportive faith or cultural context.

It is difficult for teachers to forge enjoyable, supportive relationships with children if they are obliged to use systems of control to keep them in line and to prioritise skills-based learning over play. Similarly, children are unlikely to develop resilience if they feel obliged to be compliant people-pleasers and are denied opportunities to develop self-regulation skills. Indeed, it is possible that the cultural context that our early start policy creates could itself be a significant factor in the child and adolescent mental health crisis.

Over the last year, a US film called ‘Resilience’ has been screened in scores of venues around Scotland and has elicited widespread interest (it has even been shown to MSPs in the Scottish parliament). It relates to research into the long-term effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) such as experiencing violence, abuse or neglect, which are generally more likely to affect children from disadvantaged backgrounds. The more ACEs children experience, the more likely they are to suffer from long term physical and mental health problems, and also to die earlier than non- or low-ACE-sufferers.

This research suggests that the quality of adult-child relationships during the early years of schooling is profoundly important. A relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage for three- to seven-year-olds would at least ensure that every child – however many ACEs she or he holds – has the highest possible quantity and quality of Early Childhood Education and Care … especially since play may well be a preventative factor for lack of resilience.

In November 2017, an article in the medical journal The Lancet suggested that the increase in mental health conditions among children and young people is linked to the decline of free play (especially outdoors). In the past, young children were at least able to reap the benefits of outdoor play around the edges of the school day, at weekends and in the holidays. But lifestyle changes mean that freedom for youngsters to play outdoors is nowadays severely curtailed.

It is, in fact, highly likely that a too-early school starting age is itself an ACE. A recent US longitudinal research study7 linked early formal education (i.e. before the age of six) to lower overall educational attainment, poor mid-life adjustment and increased mortality risk. The subjects of that study were not from disadvantaged homes but middle-class Californian children who were considered ‘intelligent and good learners’. Other studies have, however, focused on disadvantaged children, and have found an early start on academics to be associated, not only with lower educational attainment, but also with social and emotional problems by the time children were entering their teens8.

The most famous of these studies – the US High/Scope Perry Project— found that disadvantaged children who were taught formally before the age of six were, by their late twenties, significantly more likely to have problems with relationships and difficulty in holding down jobs. They were also more likely to have been involved in crime and less likely to vote. In the light of this, it is possible that a too-early start at school may also detract from children’s chances of becoming ‘responsible citizens’ and ‘effective contributors’.

PLAY VERSUS TESTS FOR THE UNDER-SEVENS

The case for relationship-centred, play-based learning during the early years grows stronger every day. European countries with kindergarten provision to age six or seven are not only ahead of Scotland in the educational charts (see below) but they also do better in international surveys of childhood well-being. In January 2018, Cyprus (one of the 12% of countries worldwide which, like Scotland, sent children to school the year they turn five) raised its school starting age to six. There may also be a temporal connection between the introduction of a play-based early years curriculum for three-to six-year-olds (Aistear) in Ireland between 2006 and 2009 and the success of Ireland’s 15-year-olds in the most recent PISA charts of educational attainment.

Over the last few years, increasing awareness of the factors described in this paper has led to an upsurge of interest in Scottish primary schools in translating the principles outlined in Curriculum for Excellence’s Early Level into practice. Since CfE (and its follow-up document Building the Curriculum 2) states that these principles may be extended beyond the age of six for children who still need a play-based approach, some schools are also looking at introducing play-based pedagogy in P2.

This greater appreciation of the role of relationships and play in early child development has also led to increased interest among teachers in children’s rights (based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child), including

-Article 3: that adults’ primary concern should be the best interests of the child

-Article 29: that education must develop each child’s personality, talents and abilities to the full

-Article 31: the child’s right to play.

But then this year, just as Scotland seemed on the brink of real change in early primary practice, the government introduced the new testing regime. The educational ethos behind a rights-focused, relationship-centred, play-based approach is fundamentally at odds with the imposition of skills-based, standardised tests and targets at such an early age. There are already reports of P1 teachers being told to do everything they can to ensure their classes perform well on the tests, despite all the evidence showing that any short term academic gains will be at the expense of children’s long-term educational success, health and well-being.

But then this year, just as Scotland seemed on the brink of real change in early primary practice, the government introduced the new testing regime. The educational ethos behind a rights-focused, relationship-centred, play-based approach is fundamentally at odds with the imposition of skills-based, standardised tests and targets at such an early age. There are already reports of P1 teachers being told to do everything they can to ensure their classes perform well on the tests, despite all the evidence showing that any short term academic gains will be at the expense of children’s long-term educational success, health and well-being.

Submissions to the Scottish Parliament Education Committee when they introduced the policy included a paper from Professor Cate Watson of Stirling University’s School of Education, which stated:

‘Testing may result in lowered motivation and disengagement with learning among some groups of pupils. Testing may result in a narrowing of the curriculum and the widely recognised phenomenon of teaching to the test. Testing itself can lead to stress and anxiety in pupils which potentially undermines other elements of the National Improvement Framework in relation to pupils’ health and wellbeing.’

Among the same submissions, a paper from the Educational Institute of Scotland stated that the Scottish government had not provided any evidence about how the new tests would help close the attainment gap between rich and poor and described the approach as ‘ill-judged and disproportionate’ and ‘at variance with international research evidence.’

CAN TESTS CLOSE THE GAP?

It is accepted that, if teachers feel obliged to ‘teach to the test’, most children will comply and their performance on tests of literacy and numeracy skills will probably improve, at least in the short term. The improvement is likely to be greater for children from high-income, as opposed to low-income, homes because they have an initial advantage in terms of problem-solving and language skills, and probably more well-informed parental support.

Nevertheless, as long as teachers focus on raising attainment in literacy and numeracy, the data collected will almost inevitably show short-term gains at a national level. It’s these short-term gains on highly specific tests that have driven English and US politicians to continue tightening the screws of their national testing regimes, in pursuit of ever more data. Meanwhile, however, the social mobility which a tests-and-targets agenda is supposed to encourage has not come about. Instead the poverty gap has widened.

What’s more, alongside this widening poverty gap, there has been a steady and alarming increase in child and adolescent mental health problems. These problems tend to be greater among children from low-income backgrounds, who are likely to experience more ACEs than those with more material advantages. But the ‘childhood mental health crisis’ is intensifying day by day and now affects Scottish families across the social classes.

WHAT SHOULD SCOTLAND DO?

Education is necessarily a ‘bottom-up’ process. If the foundations are strong, the entire edifice is more resilient. By giving all our children the best possible chance during their formative years of becoming successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors, Scotland could eventually achieve all four priorities listed in our National Improvement Framework:

- Improvement in attainment, particularly in literacy and numeracy

- Closing the attainment gap between the most and least disadvantaged children and young people

- Improvement in children and young people’s health and well-being

- Improvement in employability skills and sustained, positive school-leaver destinations for all young people.

To achieve these shared ambitions, Scotland should now:

1. Cancel the literacy and numeracy testing for P1 children

By withdrawing national assessments and academic benchmarks for P1 and endorsing the play-based pedagogy outlined in Curriculum for Excellence’s Early Level and Building the Curriculum 2, the Scottish government could create a new cultural climate. There is still time for Scotland to avoid falling into the tests and targets trap.

2. Recognise the importance of relationship-centred, play-based pedagogy for three- to seven-year-olds

This would give all children the time, space and support to embed the foundations of the four capacities. It would be a far more significant political move than data-collection about small children’s literacy and numeracy skills, especially when so many questions hang over the usefulness of the data in question. In the light of lifestyle changes over recent decades – particularly the decline of outdoor free play – focusing on all-round development during the early years, rather than trying to accelerate specific academic skills, has enormous long term advantages in terms of health and well-being.

3. Promote relationship-centred, play-based learning during the early years as a key element in the ambition to close the attainment gap

Early attention to the development of physical, social and emotional health and well-being (including self-regulation and resilience) is more likely to create a ‘level playing field’ for those whose family background puts them at an initial disadvantage. While the ingrained problems of poverty cannot be solved by education alone, the international evidence suggests that a later start on formal learning is more successful in the long term than homing in on the 3Rs from the age of four or five.

References

- The Gift of Time: School Starting Age and Mental Health, Thomas Dee and Hans Henrik Sievertsen, 2015 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21610 For other relevant studies, see www.upstart.scot Evidence section

- Third Force News, March 2017: ‘Scotland’s children facing a mental health crisis’ http://thirdforcenews.org.uk/tfn-news/scotlands-children-facing-a-mental-health-crisis

- Children learning to read later catch up to children reading earlier, Sebastian Suggate et al http://web.uvic.ca/~gtreloar/Articles/Language%20Arts/Children%20learning%20to%20read%20later%20catch%20up%20to%20children%20reading%20earlier.pdf

- Evidence summarised in Baseline Assessment: it doesn’t add up, Alice Bradbury, Pam Jarvis, Cathy Nutbrown et al 2018, for More Than A Score. https://neu.org.uk/sites/neu.org.uk/files/Baseline_Assessment_it_doesnt_add_up.pdf

- See UNESCO Early Childhood Education and Care. https://en.unesco.org/themes/early-childhood-care-and-education

- Closing the Attainment Gap in Scottish Education, Edward Sosu and Sue Ellis, 2014 for Joseph Rowntree Foundation https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/closing-attainment-gap-scottish-education

- Early educational milestones as predictors of lifelong academic achievement, midlife adjustment, and longevity, Margaret Kern and Howard Friedman, 2008 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2713445/

- e.g. studies cited in section headed ‘Longitudinal studies showing no long-term educational advantage and significant social and emotional disadvantages to early schooling’: Evidence section of www.upstart.scot

Download PDF version here